Building envelope testing is an important quality control measure for nearly all construction projects, but there are times when pursuing envelope testing does not make sense because it is not adding value to the project. More and more project leaders are testing their windows, roofs, and air-vapor barriers to ensure that their building is air- and water-tight. As the industry sees an increase in testing, there is also an increase in tests being applied in the wrong way or in situations that don’t make sense. From tests being specified for the wrong system to the right test being applied to an incomplete system, it is important to understand how a test can fail before it begins.

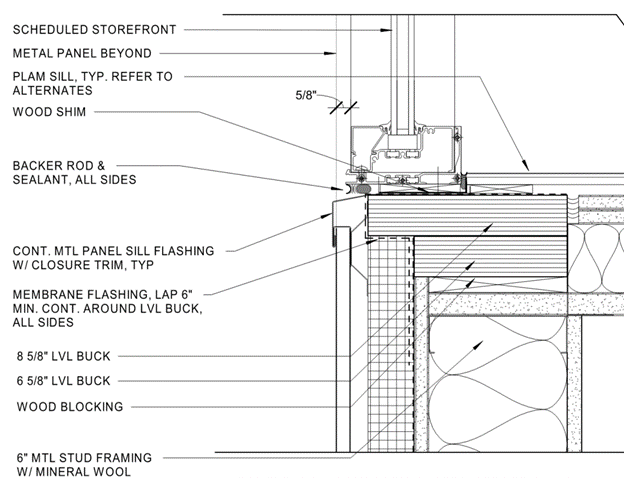

One of the common mistakes when envelope tests are specified is “canned language.” That is, generic language that travels from project to project as a holdover from some original spec produced long ago. It is not feasible to write a completely new specification for each project, so it is fine to carry over most of the language without much detriment to each new project. In some instances, however, the “canned language” that is carried over simply does not make sense. A common example is AAMA 501.2 Quality Assurance and Diagnostic Water Leakage Field Check on Installed Storefronts, Curtain Walls, and Sloped Glazing Systems. As the test name states, it is applied to various types of windows (storefronts, curtain walls, etc.) rather than a metal panel system. It is somewhat common to see this test specified for metal panels or a rain screen system. Let’s look closer to see why this test would “fail” when applied to a metal panel system. Per AAMA 501.2, the test standard is based on spraying water at “joints, gaskets and sealants details in the glazing.” As water is being sprayed from the outside, an observer is inside watching for leaks. Leaks are easy to spot because the window is the only component separating the interior from the exterior. A storefront or curtain wall is a unique building envelope component because it separates the interior from the exterior using much less material than most other areas. Take a typical wall with metal panels attached to the exterior, for example. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: a drawing detail showing a storefront and a metal panel system.

There is the substrate, air-vapor barrier, mounting hardware attached to the substrate, and insulation detailed around all the mounting hardware. The metal panels then attach to the mounting hardware. Not only is this system designed to shed water, but it would be extremely difficult to spot water on the interior because it would have to make its way through multiple systems. Further complicating things is that the observer on the inside would not know where water is being sprayed on the outside. In this case, the test has been specified for the wrong system and is therefore not adding value to the project.

Following the project specifications is important for constructing the building correctly. There are times when following the specifications, particularly with building envelope testing, will not produce the best possible results. One such instance arose when two tests were specified to be performed sequentially. The first test, ASTM E 1186 Standard Practices for Air Leakage Site Detection in Building Envelopes and Air Barrier Systems, was specified to be performed prior to the second test, ASTM E 783 Standard Test Method for Field Measurement of Air Leakage Through Installed Exterior Windows and Doors. The first test would show where air is leaking, and the second quantifies how much air is leaking. Window manufacturers, however, allow a certain amount of air leakage. In this case, the allowable leakage is 3 CFM. Performing ASTM E 783 first allows the project team to determine if the amount of air leakage is problematic. If the air leakage is above the allowable limit, then ASTM E 1186 could be used to troubleshoot the window. Let’s say you perform ASTM E 1186 first and discover air leakage in a specific location. Then you perform ASTM E 783, and the leakage only amounts to 2 CFM. Since the leakage is within the allowable limits, the first test to determine the location was unnecessary and did not provide useful information. Building envelope tests are meant to provide useful information about whether a system is performing the way it is intended to. By applying these tests without considering what information each test provides, a project team may be wasting time and money discovering information they do not need.

There are situations where the right test is applied to the right system, but the project itself is not a good fit for envelope testing. The most common example of this is when a project team tests new windows that have been installed in an old building. When testing storefronts or curtain walls, the test typically incorporates the window and the perimeter seals where it connects with the air vapor barrier. On new construction projects, the building will be designed to have a weather-proof enclosure which ties together the foundation waterproofing, air-vapor barrier on the walls, and the roof to create one system. Windows are also designed into this system so that when installed correctly, the building envelope is continuous. Old buildings were not designed this way. Instead, old buildings were designed to dry out after taking on water by allowing air and vapor to move across or through exterior walls. A common retrofit for old buildings is to install new windows to reduce drafts and increase energy efficiency. When a test is applied to these windows, such as ASTM E 1105 Standard Test Method for Field Determination of Water Penetration of Installed Exterior Windows, Skylights, Doors, and Curtain Walls, by Uniform or Cyclic Static Pressure Difference, it is testing an incomplete system. There is one component designed to be water-tight surrounded by construction, a brick wall for example, that is not. When a water penetration test is applied to an old building as if it were new, the results can be confusing. If water is seen coming into the interior side, the project team may conclude that their window is leaking when in fact the surrounding brick is taking on water as it normally would. Is the project team then going to start tearing apart the existing brick wall to determine the exact path of the leak? If yes, what repairs are reasonable given that there are likely dozens of windows with the same condition? A misinterpretation of results from an incorrectly applied test can quickly lead to wasted time and money.

Building envelope testing is one of the best assurances that individual components have been installed correctly to form a complete and continuous system. It takes an experienced project team and testing agency to ensure that the specified tests are applied in a way that adds value and provides useful information. It is important to ask, “What is the intent of applying this test?” and “Is this test being applied correctly for this project?” Simply trying to meet the specification or throwing tests at a project without considering what will be accomplished with each test is an easy way to waste time and money. By considering what the test is for and how it is applied, a project team can prevent a test from failing before it begins.

Contact us or click here to learn more about our envelope testing services.